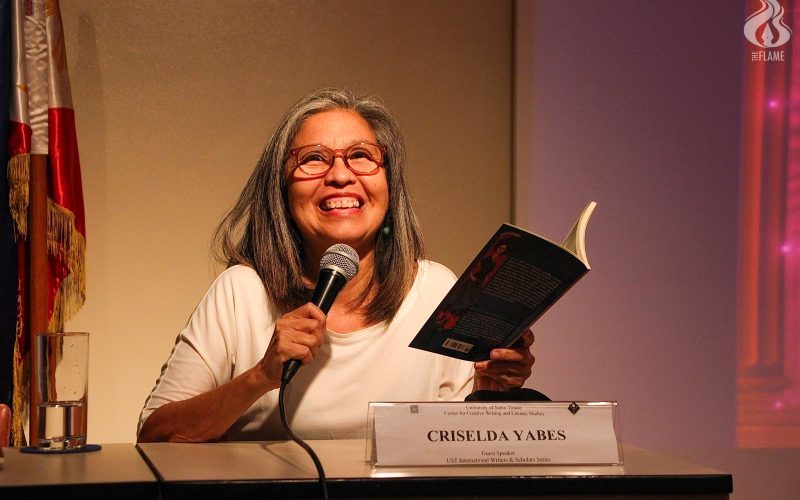

Imagining a frightening future for Filipinos

MANILA, Philippines – One tale is set in 2050. The other in 2069. Both paint a dark, frightening future for the Philippines.

In Criselda Yabes’ Barcelona, Manila is a sinking, dying city. Manila Bay and the West Philippine Sea are slowly, steadily claiming a metropolis reeling from violence and chaos.

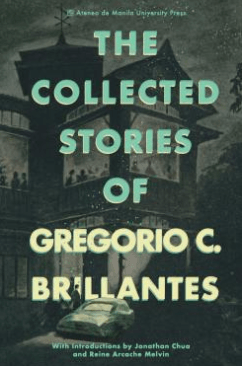

In The Apollo Centennial, Gregorio Brillantes imagines a society in the grips of high-tech authoritarian rule and a repressive social order imposed with a bastard language.

The Apollo Centennial was part of the recently-published The Collected Stories of Gregorio C. Brillantes, which won this year’s National Book Award for short fiction. Barcelona was the other finalist.

‘Barcelona’: Dying, sinking Manila

That Greg and Cris were honored was a pleasant surprise, and a stunning coincidence for me. They’re both writers I admire greatly. Greg is a friend, mentor and former editor. Cris, also a friend, is a fellow UP Diliman alum and one of the best journalists of my generation.

Reading Cris’ novel made me remember Greg’s brilliant short story. That’s because both stories imagine a terrifying tomorrow.

In Barcelona, armed groups battle it out for control of the crumbling capital drowning in the terrifying consequences of climate change and societal meltdown.

One of them, the Ulilas, is led by Barcelona, a survivor of the Duterte Slaughter and the pandemic. Her army of orphans are in a life and death struggle with the Pogos, the criminal gang that aims to turn them into slaves — and with a city whose time is running out.

Aris, a young officer from another army led by Cezar based in another part of the country, has traveled to Manila for a mission: to convince Barcelona to abandon the sinking metropolis and join a movement fighting for a better future in the southern edge of the archipelago.

“My mission is to bring her South where we can begin a new country … Today, there is an urgency, with the islands around us sinking, another curse plaguing a god-awful country.”

But despite the atrocious conditions Barcelona and her army endured in the crumbling capital, convincing her to abandon Manila wasn’t going to be easy.

“How can she stay in this squalor. … How stupid of me to think this is going to be easy. This is her home. She was born in misery. Her father turned to selling illegal drugs because of their poverty. … From the Drug War to the coming of the Virus, it must have been the end of the world.”

“How much worse can it get seeing the city you survived sinking to the bottom, literally in more ways than one? And the skirmishes she’s had with the Pogos trying to steal her people as if they were medieval savages.”

‘The Apollo Centennial’: The world of Tagilocan

The Apollo Centennial tells a quieter tale. But it portrays just as troubling a future.

A century after the historic Apollo 11 mission, there are celebrations of the momentous event, including in an unnamed Philippine city. It is a celebration of technology at a time when technology has morphed into a weapon of domination and repression.

As the story begins, we see Arcadio Nagbuya and his sons and the schoolteacher Mr. Balaoing waiting by the river for a raft that will take them to the road where they can take a bus to the city to see the Apollo exhibit.

There are glimpses of the new order during the trip.

The school teacher reads a magazine article on the exhibit. The article is in Tagilocan — Tagalog plus Ilocano — the country’s dominant language at a time when other languages have been suppressed or have died.

At one point during the trip, Arcadio Nagbuya encounters a disturbing scene.

“Now the sky is clear but for the remote clouds, and a couple of helidsics humming in a wide arc over the fields. For a moment the fighter-bombers hang gleaming in silhouette against the mountains, their two-man crews visible in bubble canopies, before rising vertically, abruptly, cut off from view by roof of the bus.”

“Something like the premonition of a terrible and swiftly approaching disaster alights on Arcadio Nagbuya’s heart, but Andres, he assures himself, knows what he is doing.”

At a checkpoint, a lieutenant directs a soldier to search three young men and “to look closely at their index fingers, for the tell-tale grooves formed by the triggers of Nasakom pistols.”

As the bus leaves the checkpoint, the schoolteacher reacts: “Robbers and fascists,” Mr. Balaoing cranes his neck to peer spitefully at the receding outpost, and then meeting Arcadio Nagbuy’s neutral gaze, shakes his head and slumps back in his seat.”

Technology terrorism

The Apollo Centennial was published in 1980. Six years later, fears of an authoritarian future faded with the fall of the Marcos regime.

But the dark past, the worldview that gave rise to tyrants, roared back with a vengeance, propelled by that powerful tool: technology.

I began to realize this in 2009 when I wrote about The Apollo Centennial on the occasion of the moon landing’s 40th anniversary. The World Wide Web, then in its 20th year, was a magnificent tool for bringing people from all over the globe together — including conspiracy theorists and agents of disinformation.

Most of the reactions to my article were from people who believed passionately that the Apollo moon landing never happened.

Things have only gotten worse.

We’ve endured a grim decade marked by the rise of Dutertismo and Trumpism, the brazen distortion of reality and history, even as the world reeled from the devastation caused by climate change and the pandemic.

‘What we have done to ruin our country’

Cris, who grew up in Mindanao, wrote Barcelona during the early months of the COVID-19 lockdowns, when she felt “distraught by the fact that I was stuck in Manila even though I’ve been living in this city for about 15 years.”

“I put everything together, my thoughts on politics, the idea that we’re doomed, that we have to reboot, and that it can’t go on like this anymore if we’re to survive the pandemic,” she told me.

“I remember having read an article online about parts of Manila sinking by 2050 and I used that as the trope, I also wanted it to be a warning about climate change, our lack of moral compass, our destructive political and social system. All that from the eyes of a young man who was born after the apocalypse and had to rescue Barcelona, who herself is a symbol of the remnants of our old country. I included some bits of facts about our history — Rizal, Bonifacio, Magellan — all of which meant nothing because of what we have done to ruin our country. “

Hope in resistance

Barcelona and The Apollo Centennial are ugly portraits of the future. But the stories are also about hope and resistance. About hope in resistance.

“When this is all over, I will show you Barcelona, the rainbow over our islands,” Aris says. “There are no birds in your dark city, Barcelona. Join us in the light and the birds will be singing to you. We’ve got plenty, you won’t believe it.”

I sometimes still find myself rereading the subtly moving final section of The Apollo Centennial, which I consider one of the best short stories I have ever read.

On the return trip home, Arcadio and his sons take the raft once again. Arcadio sees a passenger “cradling a laser rifle wrapped loosely in a raincoat.”

This is Andres, the man whose safety he was worried about. He is Arcadio’s cousin.

When he sees Andres, “the dim oppressive fear surrounds his heart as he remembers the helidiscs hunting over the morning fields. His cousin clicks off the flashlight and speaks to him, not in Tagilocan, but in the old language. … They were young boys together once: how quickly the years pass.”

The cousins greet each other and shake hands. We need people, Andres says.

“The tender fluid accents of their fathers’ tongue, unheard for so long yet never quite lost nor forgotten, bring a swift rush of pride and love that pushes back the enclosing dread.”

We hope you can join us, Andres says. Then the cousins part ways.

Big truth of fiction

When the finalists for the National Book Award for short fiction were announced, Cris said: “It won’t take a wild guess who the winner will be,” Cris Yabes wrote in a Facebook post. “I’m honored enough to be alongside one of the most esteemed writers my country has ever produced.”

I agree.

Greg, a dear friend and mentor, is undoubtedly one of the best writers the Philippines has produced. He should have been named National Artist decades ago. More than 40 years after we worked together when I was just starting my career, I still remember and value everything he taught me about writing.

But Barcelona underlines Cris standing as one of the foremost and most original storytellers of my generation.

She’s a veteran journalist who has covered the coups in the post-Marcos era in the 1980s, the scary encounters on Sniper Alley in Sarajevo during the Balkans War in the 1990s, and has written critically-acclaimed novels and nonfiction reportage on the seemingly endless conflict in her native Mindanao. [READ: The military’s wrong war]

Journalism is a fun and exciting world. But Cris has gone beyond all that, taking what the novelist John Le Carré called the “small truth” of journalism to explore the “big truth” of fiction. – Rappler.com