Spies, Lies and Allies: A tale of two forgotten revolutionaries from Bengal

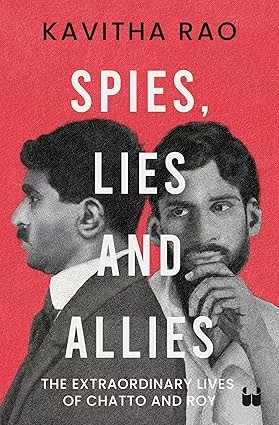

My dip into the newspaper archive was prompted by Kavitha Rao’s recent book, Spies, Lies and Allies: The Extraordinary Lives of Chatto and Roy, where she paints vivid portraits of Virendranath Chattopadhyay (1880-1937) and M.N. Roy, two extraordinary lives that ran parallel through times of hope and turbulence. I wanted to think through two premises that animate Rao’s project: first, that “Chatto” and Roy were, in scholar Sudipta Kaviraj’s words, “magnificent failures”; second, that they are forgotten figures.

Without lapsing into vague relativism, what could be the parameters for defining success or failure in these realms? And how do we identify the public—or indeed publics—which remembers, forgets and re-learns about such figures from history?

With a self-conscious hat-tip to Frederick Forsyth’s political thriller, The Day of the Jackal, Rao begins Spies, Lies and Allies with a man facing a firing squad. Her setting is Moscow, on 2 September 1937. Chatto, one of over 700,000 political opponents to be killed during Stalin’s infamous purge, had been described by journalist and “triple agent” Agnes Smedley as “a revolutionary in a dozen different ways.” Rao speculates evocatively about what must have been passing through Chatto’s mind: his happy childhood, his homeland to which he had not returned in decades, his travels and travails in different parts of Europe at a singularly volatile time in history. Or did he think enviously, Rao wonders, “of his fellow revolutionary, the dashing and charismatic M.N. Roy”, who had, by securing Lenin’s friendship, beaten Chatto in achieving his dream?

The two parallel lives are traced in alternating chapters. Chatto’s begins at their family home in Hyderabad, where secularism and learning were held in high regard. Drawing primarily on the memoirs of his siblings, the freedom fighter Sarojini Naidu and poet and actor Harindranath Chattopadhyay, the chapter focuses on the patriarch, Aghorenath, rather than Chatto. The notable exception is the initial episode, where notorious British police officer Charles Tegart ransacks their house in search of a compromising letter from Chatto.

Roy’s early days are told primarily through the region’s political climate, reflected in the revolutionary zeal of figures like “Bagha” Jatin, or Jatindranath Mukherjee. (The first chapters refer to Roy by his birth name, Narendranath Bhattacharya, which he changed after landing in the US while on the run.) Compared to her portrayal of the Chatto household, Rao’s sketch of the Bengal landscape feels less immersive, despite being politically charged, perhaps owing to the nature of the archive the author relies on.

One notices three distinct movements in the book. The first, beginning with the protagonists’ youth, goes on to trace their formative years into the mid-1910s. These are marked by a distinct note of optimism, as Chatto and Roy encounter a fascinating cast of characters and collectives in their attempts to secure help for India’s anti-colonial struggle.

<img id="11745576091535" class="lozad storyEmbedImg" data-src="https://www.socialmediaasia.com/wp-content/uploads/p5book_1745576090584.jpg" alt="By Kavitha Rao, Westland, 256 pages, ₹499″ title=”By Kavitha Rao, Westland, 256 pages, ₹499″>

View Full Image

Chatto’s path takes us to India House in London, where he meets its founder, Shyamji Krishna Varma, and a young V.D. Savarkar, among others, while Roy travels east to Japan, only to be disappointed by fellow revolutionary activist Rashbehari Bose’s uncritical faith in Japan. A thrilling cat-and-mouse game ensues when Roy, on his way to China to secure arms from the German embassy, is tailed by the British police. Unable to convict him, they advise: “There are many revolutions in these parts. Stay away from them.”

In the second movement, both Chatto and Roy begin to find footholds in unlikely political networks during and in the aftermath of World War I. Chatto begins to operate out of Berlin, where, aided by German lawyer and diplomat Max von Oppenheim, he becomes involved with the Berlin Committee (later, the Indian Independence Committee), and has a brush with the pan-Islamist movement.

I found the chapter on Agnes Smedley one of the most nuanced in the book, as it opens up to scrutiny the problematic gender dynamics within revolutionary spaces from the perspective of a person with her own share of complexities. In fact, the book has a number of well-crafted cameos, like Bhikaji Cama, Jack Johnson and Oppenheim. The alternative vantage points afforded by these inclusions allows us to see the two protagonists from different perspectives and perhaps, more significantly, sheds light on a frenetic internationalist moment of many potential solidarities, which often falls by the wayside in mainstream narratives of India’s freedom movement.

Meanwhile, Roy, thinly disguised as a Tamil student on his way to Paris, lands in New York, amid a “teeming nest of Indian revolutionaries”. A question from the audience at a public lecture by Lala Lajpat Rai prompts him to reassess his understanding of Indian independence: was the discourse around independence overlooking the hope of a truly revolutionary class struggle? Rao describes Roy’s dive into Marxist philosophy at the New York Public library and his involvement with the Ghadar Movement, leading to his arrest in 1917.

The journey continues in revolutionary Mexico, where Roy meets Mikhail Borodin a couple of years later. This “internationalist” phase sees him representing the Mexican Communist Party at the 1920 Comintern (or IIIrd International), and founding a Communist Party of India in Tashkent, along with Abani Mukherjei and others.

Despite their commitment and brilliance, Roy and Chatto have fallen between the cracks of narratives that later coalesced as “history” in the public imagination.

The pace becomes feverish in the third movement, as a frantic race to secure Russian support for the Indian cause ensues. Roy beats Chatto to secure Lenin’s support, although he disagrees with the latter’s insistence on working with the Indian National Congress (INC). Roy eventually meets Stalin and ends up on a doomed mission to China with Borodin, from which he escapes narrowly. Chatto, who had hoped that the INC would work with workers’ and peasants’ organisations, finds his relations with Jawaharlal Nehru failing disastrously. Nehru, believing Chatto to be unmoored from the ground reality, favoured INC solidarity above all else. Roy would return to India and spend over five years in jail, before founding his new philosophy of Radical Humanism. Chatto would face the firing squad eventually, unbeknownst even to his family and friends.

Rao’s positioning of these two charismatic individuals as forgotten figures piqued my curiosity because, in my experience, Roy is a household name within left-leaning or indeed politically aware circles in India. (Roy even had his own first day cover in 1987.) So is Chatto, though to a lesser degree. How then do we understand the amnesia around them in their native village, in their family or, for that matter, within mainstream political discourses?

Despite their commitment and brilliance, Roy and Chatto have fallen between the cracks of narratives that later coalesced as “history” in the public imagination. They were conducting their own experiments with truth as—to recall Antonio Gramsci’s words—the old world lay dying and a new one was struggling to be born. Their faith in ideas, ideals and ideological solidarities may have seemed justified at the time but the nationalist movement in India took its own course, particularly in the aftermath of World War II, which got in the way of their vision bearing fruit in the political realm. Rao’s book, which speaks disparagingly of Nehru and M.K. Gandhi’s “mealy-mouthed compromises with the British” intervenes by carving out a space for two forgotten individuals within public history.

Read as two biographies, it leaves one wishing for a deeper dive into the people themselves, but through the juxtaposition of the lives, Rao achieves a good deal more. The book is a reminder of those phases in history that are pregnant with the possibility of multiple worlds; what becomes the “public” narrative is retroactively constructed from the vantage point of the new world that emerges eventually, often at the cost of other memories. It is that forgetting which Rao sets out to address here.

While her admirable effort did leave me wondering if a closer engagement with primary archives (alongside autobiographies, biographies and scholarly work) could have made the history feel more tangible, Spies, Lies and Allies succeeds in establishing the importance of including those who “failed” and were “forgotten” within the grand narrative of the nationalist movement.

Sujaan Mukherjee is a Kolkata-based researcher, translator and curator.