Kids who wait for big rewards are more likely to do well in school

Children who are better in delaying gratification are more likely to do well academically and have fewer behavioral problems, according to a new study.

Suppose you were given a choice between having a smaller reward now and getting a larger reward 10 minutes later. For most adults, the choice is clear. Withstanding short-term temptation in pursuit of a greater long-term goal is crucial for the functioning and well-being of individuals and society.

While the famous “Marshmallow Test” developed by Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel in the 1960s has pioneered a large body of research on delayed gratification in Western populations, little is known about how well other tasks can measure young children’s ability to delay gratification, particularly in the Asian context.

The new study by Chen Luxi and Professor Jean Yeung from the National University of Singapore’s Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, modified and validated a different task, called the choice paradigm, to measure delay of gratification among Singaporean young children and examined the factors behind the development of delayed gratification and its longitudinal outcomes.

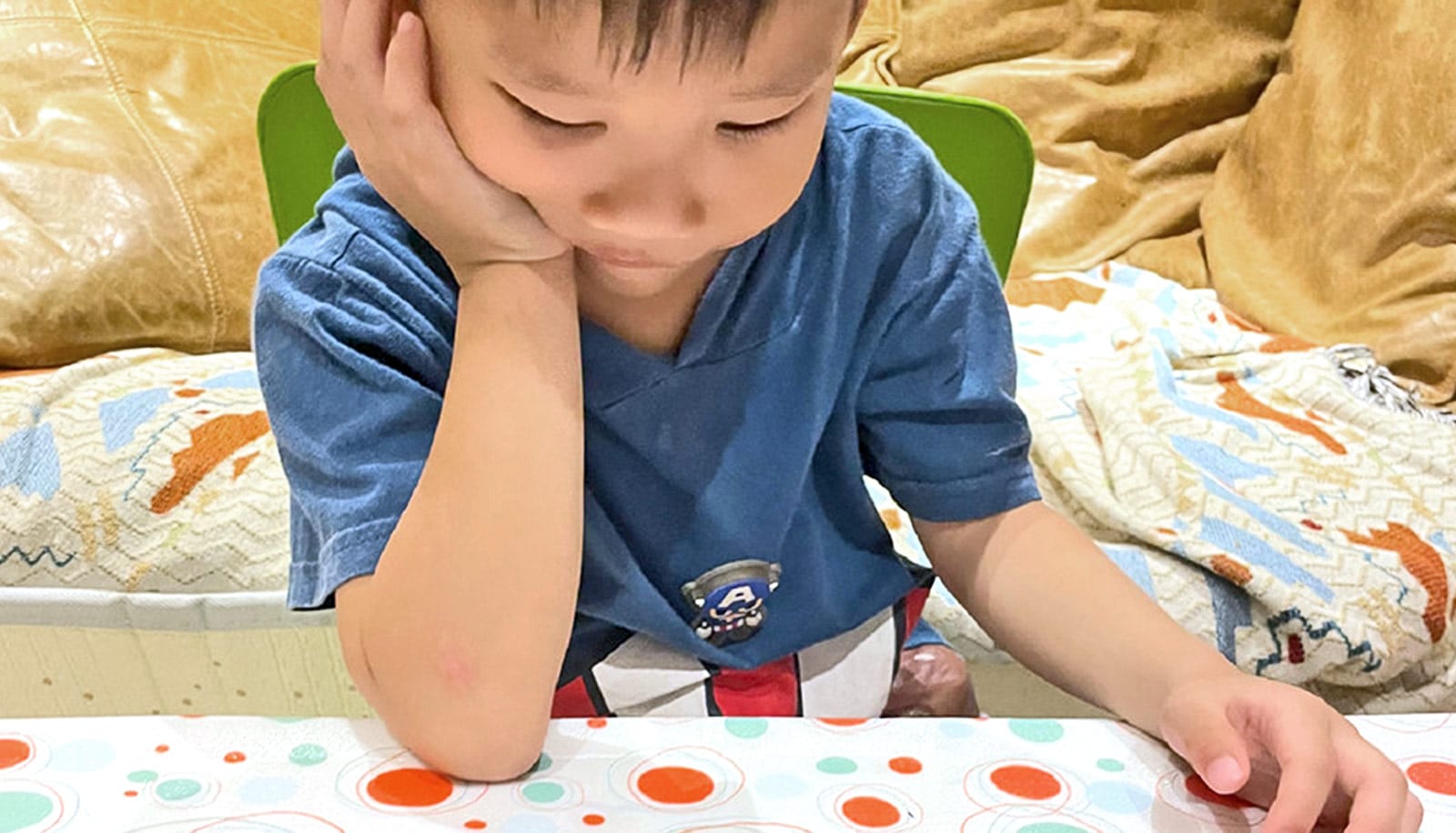

In the choice paradigm, children were presented with both the “now” and “later” options simultaneously. They made choices between getting the smaller reward immediately and getting the larger rewards 10 minutes later, over 9 test trials.

This study sheds light on the development of self-regulation among Asian children to address the gap in research in this area, which has predominantly focused on the classic marshmallow test and Western populations.

Nationally representative data used in this study were part of the Singapore Longitudinal Early Development Study (SG-LEADS), led by Yeung, funded by the Ministry of Education Social Science Research Thematic Grant, and housed by the Centre for Family and Population Research at the NUS Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

As a modern and affluent nation with a highly educated, multicultural, and multiracial population, Singapore serves as a useful case study for valuable insights into the development of children from other Asian societies with similar characteristics.

Close to 3,000 Singaporean preschool children were tested in two waves—the first assessed children’s working memory, delay of gratification indexed by the choice paradigm, as well as parent-rated children’s self-control in their daily lives. The second wave two years later saw roughly the same batch of children being studied for academic achievement and behavioral issues. The results were interesting—age, gender, and parental education were the factors found to influence a young child’s ability to delay gratification.

Preschool girls were found to have generally outperformed preschool boys during the delay of gratification choice task. While girls generally made future-oriented choices at age four, boys started to delay gratification later at age five.

Chen and Yeung also discovered that children of parents with lower education backgrounds started delaying gratification at an older age. The findings suggest the role of socioeconomic environments in nurturing children’s ability to delay gratification during early childhood.

The data further revealed that children who show greater self-restraint and willingness to delay their gratification in their preschool years also tended to have better working memory and self-control which were linked to better academic skills and fewer behavioral and emotional problems two years later.

“The findings have practical implications,” Chen says. “It revealed that having greater self-regulation in early childhood, including having a greater ability to delay gratification, more advanced working memory, and stronger self-control in their daily lives, can predict children’s more excellent academic achievement and positive behavioral development later in life. Our findings underscore the importance of incorporating self-regulation into future interventions and educational programs.”

“It is crucial to nurture children’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral self-regulation during the preschool years, so as to enhance their school readiness and build a good foundation for their socioemotional functioning and academic skills in formal schooling,” she adds.

Source: National University of Singapore